Amidst Accra’s heavy Monday morning traffic, on this day, worsened by dawn rain, we are caught up in the common yet arduous experience of extended waits for the next available Trotro (minibus share taxis) to no end. Taller, one of these notorious ‘roadside legends’, on one hand is busy operating what looks like a personal seat reservation service, ridiculously protecting front row seats for passengers, Trotro by trotro—as if they had an exclusive pre-booking arrangement with a day before. For us who did not have the Ghanaian ‘whom you know privilege’ that Taller offered, fighting our way through these unclaimed seats while trying to evade skilled pickpockets was the way out. Alternatively, you may use your masculine strength to push your way through to survival seat, revealing nuanced gender dynamics hidden in our transport sector.

It is apparent that with our growing urban population, issues of access, affordability and limited transport alternatives is what is primarily steering our dependence on tro-tro a.ka. mini-buses. In fact, findings from Global think tank, Copenhagen Convention Center reveal that 70% of Accra’s urban population use these ageing minibuses, shuttling in a daily dance of destinations. Despite numerous plans to usher in a modernised transportation system like the Bus Rapid Transit system, these endeavours have evidently failed, with the 2007 World Bank and GEF Trust’s USD 52 million Grant Urban Transport Project(UTP) yielding little results.

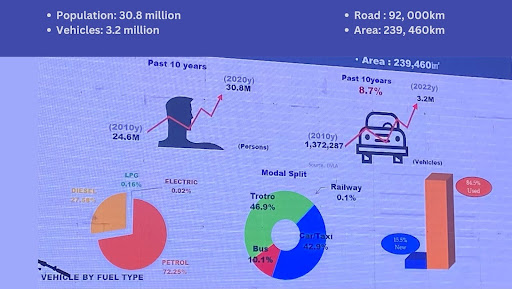

The fragility of our public transport system has on the other hand encouraged many city dwellers to opt for their own private vehicles. In the last decade alone, private car ownership has increased from 1.3M to about 3.2M sustaining the trend of politics of mobility – where controle of a steering wheel of an automobile symbolises social power, class and opportunity in a typical African urban domain.

Transportation as a means to move cars or a means of moving people?

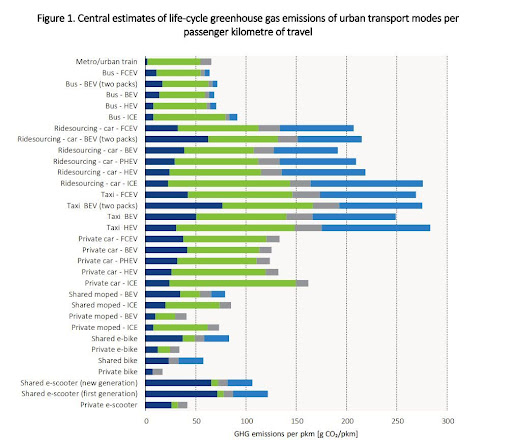

Ghana may be considered a relatively low polluter of Greenhouse Gas emissions on the global stage, however, it is often important to zoom in on specific sectors. The energy sector is obviously a major contributor to our emissions. Alone, it was responsible for a significant 35.5% of emissions in 2016 (Nyansapo, 2022). When we take a closer look at the breakdown of these emissions, it becomes evident that the transport sector is a major driver, accounting for a substantial 47.7% of energy-related emissions. Within this category, vehicles play a key role, contributing over 7.2 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent, which corresponds to about 17% of the total emissions according to the Basel Institute for Sustainable Energy at the just ended Africa Climate Week. Meanwhile, Ghana’s 2022 SDGs Budget and Expenditure Report showed an allocation of GHS4,823.35 million in 2022 to transport expansion. In our quest to address these issues, solutions should not be entrenched in the single known strategy of road expansion, noticeable in expansions happening in the metropolitan districts of Amasaman, Spintex-Palace Mall area and East Legon, definitive of car oriented cities. It is true that investments towards improving Accra’s public transport have to be addressed, however associated issues like high volumes of traffic require that in proffering solutions, we avoid maladaptive solutions that can inadvertently steer us into ineffectual outcomes. Improving transport access must mean shifting to sustainable transport modes and lower transport related Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions along the BRT corridor in Accra, addressing the common 2 hours peak-hour congestion to and from the Accra central business district which affects work productivity and stress levels accompanied with the long hours linked with non communicable diseases, ensuring our security from pickpockets during after-work rush hours, while additionally saving USD15 billion in health and economics savings and giving better air quality outcomes for a city whose air quality on average is 1.7 times above WHO standards (Ghana’s Air Quality Index of 75 is considered to be potentially harmful to sensitive individuals)

Embracing changes in the way we move around – active, shared and electric mobility options can improve the quality of our urbanlife and our environmental ecosystem

How Accra has been a leader in urban culture and technological advancement

Over the years, Accra has proven itself as a leader in cultural representation and tech advancement. As early as the 1910s, drivers in colonial Ghana embraced the opportunities presented by technological advancements. They harnessed imported motor transport technologies to advance a wide range of local, social and economic objectives within the capital, showcasing its adaptability to change. The city also established itself as cosmopolitan, fostering cultural interactions within the global urban landscape. Accra has garnered a reputation as a highly sought-after destination for students for more than two decades. In the past decade alone, virtually every prominent American university, including prestigious institutions like Harvard, Michigan, Rutgers, and Colorado, sent its students to partake in various programs in Ghana. The nine- campus University of California for example, has been running year- abroad programs in the country since the early 1990s. While New York University has a large property that regularly hosts students and professors from their campuses.

Beyond Accra’s warm hospitality and destination for diverse visitors looking to savour the essence of Africa. The City hosts the Chale Wote Street Art Festival, one of the most significant and vibrant arts and cultural festivals in West Africa making it a hub for contemporary cultural dynamism. Accra’s vibrant nightlife is also a testament to its dynamism and the fusion of traditional and modern influences. Today, Accra continues to play host to those who want to enjoy the annual December in Ghana pilgrimage. Imagine what centering Accra’s urbanscape with cycling infrastructure will do for experiences like December in Accra.

Transforming Accra to become a bike-friendly city is not just about infrastructure and transportation; it’s about building an inclusive culture via cities across the world while we accommodate people from these diverse cities. Accra’s historical adaptability to technological advancements showcases our capability to embrace cycling fully. Our role as a cultural and artistic hub are indicative of our allure as a place of social interaction that cycling offers, ensuring that residents and visitors alike engage the community in unique ways.

Negative associations linked to cycling that we must dispel

Cycling often faces different misconceptions. People will often dismiss cycling as a viable alternative, for example, the fact that you can get wet when it rains. However we can build bike bridges like the Peace Bridge in Calgary, Canada. The 126-metre-long bridge comes with a helical steel structure with a glass roof and lamps for night cycling.

We can also accompany cycling infrastructure with electric powered trains for cyclists to use when the weather takes a turn. S-trains in Europe play a crucial role in promoting cycling as an efficient mode of transport. These suburban commuter trains are designed with cycling in mind, offering dedicated spaces and facilities for cyclists to bring their bikes on board. This integration allows commuters to seamlessly combine train travel with cycling, making it easier to reach their destinations when it’s raining.

In other cycling city’s, you will find, secure and well managed public or private Bike Lockers, Racks and Shelters that serve as sanctuary facilities for bikes. In the case of unfavourable weather, you can easily stop by to park and then pick a ride-hailing service or take the regular taxi or ‘troski’.

What are the Advantages of making the City Bike-friendly?

According to the Pedestrian Safety Action Plan for the Accra Metropolitan Assembly, the average annual number of accidents in Accra is near the average for African cities (AMA 2019). However, the number of accidents causing fatalities and injuries affecting pedestrians is much higher than most other African cities, recording some of the most dangerous street accidents in the world for pedestrians (AMA 2019). Expanding the city’s transportation to include cycling can decrease the projected number of cars on the road for pedestrians as seen in the Dutch cycling cities of Utrecht and Copenhagen, since the growth of bike culture in the Netherlands, the number of road accidents has plummeted drastically and air pollution and estimated healthcare costs of $300 million annually saved over time.

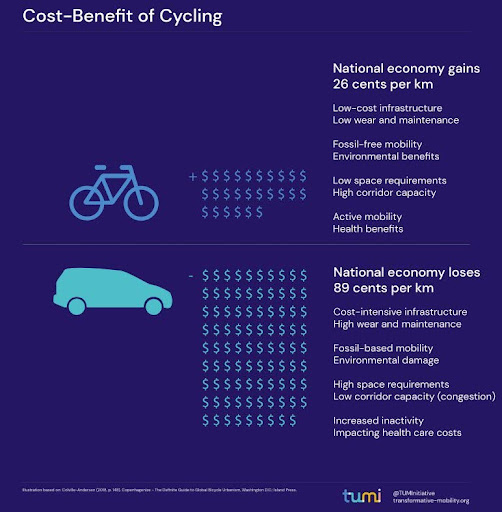

Secondly, it is more easy to manage than BRT systems like Ayalolo that have failed. Establishing and maintaining a Bus Rapid Transit system, such as Ayalolo, requires substantial financial investments in infrastructure, buses, and maintenance. In contrast, promoting cycling infrastructure, such as bike lanes and bike-sharing programs, is often more cost-effective and can be implemented incrementally. European Cities of Copenhagen and Amsterdam are examples, dedicated bike lanes, bike-sharing programs, and bike-friendly which have been implemented incrementally have required fewer extensive modifications compared to BRT systems which require significant redesign and heavy construction.

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, oil prices have seen a continuous surge, the conflict sent oil prices to near 14-year highs, with Brent crude hitting over US$130 per barrel exposing Ghana’s vulnerability to the oil price shocks. After a period of decline, there’s been another surge on the back of an increase in the international market price of gasoil by 3.33% and LPG by 2.95%, coupled by a 0.97% depreciation of the Ghana cedi against the U.S. dollar on the foreign exchange market. Fuel prices are a key driver of inflation in Ghana. In fact, the January 2022 year-on-year inflation rates published by the Ghana Statistical Services show that first, transportation (17.4%) and then, housing, electricity and gas (28.7%) are the biggest inflation drivers. Cycling emerges as a valuable solution in the face of these unbearable fuel prices and its economic consequences. It is pocket-friendly, with added benefits of healthy urban lifestyles. Electrification of urban systems, mitigation actions like active mobility will save us both economic and environmental costs.

In addition, cycling infrastructure have co-benefits of greener spaces in various ways.

If Accra invests in cycling infrastructure, it will give us the opportunity to revolutionise our city infrastructure design to incorporate green design elements like trees and parks that enhance the urban environment. For instance, in cities across Latin America and Asia, initiatives like dedicated bike lanes and cycling corridors are frequently complemented with landscaping, tree planting, and green buffers. These green additions not only beautify the surroundings but also provide valuable ecological services, such as improved air quality, urban cooling, and stormwater management creating the welcoming and inclusive spaces that hosts a number of international guests that troop into the city and encourage more people to cycle.

Ultimately, in our politics of change, the city’s most valuable resource is its human capital. Investing in clean mobility can lead to employment opportunities across various sectors, from manufacturing and assembly of electric vehicles and batteries, installation and maintenance of charging infrastructure, development of renewable energy sources for clean transportation, and encouraging entrepreneurship. One of the city’s start-ups, Wahu! has deployed about a 100 locally produced fleets of e-bikes and onboarded informal okada drivers as delivery riders, addressing informality in a $90 trillion global urban economy. The venture also has a program called Women Deliverers, that is training women riders in Lomé. In Accra, being mobile is crucial for women’s ability to work and provide for their families in their identity as modern and hardworking women. Opportunities for shorter trips through cycling provides greater gender equity which will give fibre and strength to our fragile urban cultures.

To conclude, it is important to note that we are fast moving from the era of fuel—a time of over-consumptive modernization and technological development to an era of sustainability, where technological advancement promotes both speed and shared progress for the present and future. Cities are at the centres of this cultural transformation, the most successful social, economic and cultural struggles; from women’s emancipation, voting rights, absolute monarchy to climate justice have been born, fought and won realised in cities and Accra must be no bystander.

In a study done by Alimo et al. 2022 on cycling in Ghana, it showed that many road users have interest in adopting future bike-sharing schemes. Indeed, many City dwellers want to bike to work, school etc. This is however dependent on right cycling infrastructure and policy change that respect cyclists as equals. The findings reinforce the need for a National Cycling Policy Framework to accompany the National Electric Vehicle Policy which is currently under preparation.

We must also set up a strong institutional basis for coordinated planning and regulation. The World Bank report Cities on the Move (2002) identified institutional weaknesses as the source of many observed failures in urban transport in developing countries. While the Accra Climate Action plan is a roadmap for an inclusive city we must broaden a wider city vision that accommodates active mobility needs of travellers and not vehicles only.

Cycling is the equity angle in our cities. The reality is cycling-friendly urban landscapes in successful cities have been mostly citizenry led. It is us citizens who intimately understand our needs and preferences when it comes to transportation and better air quality and health outcomes. We know the local terrain, traffic patterns, and where cycling infrastructure is most needed and it is time to build a strong advocacy community that can influence policy decisions, and raise awareness about the myriad benefits of cycling.All these considered, true transformation is possible only when there’s integrated levers of governance, finance and technology mechanisms. Partnership is what firms these levers up. An example of the partnership needed is what Impact Hub is trying to exemplify with the Net Zero Accra platform, facilitating partnerships and collaboration with actors shaping the mobility ecosystem in the City, from auto-makers, indigenous start-ups, corporates and non-governmental organisations but we also need greater multilateral partnerships that puts finance at the center to support governments to leapfrog. Even as we do so, we must remember that while a chunk of national finance comes from urban Accra, finance is generally not localised and controlled by local governance enough, we need to decentralise finance to fully establish Accra as the cycling city of Africa.

References

- Maya Møller-Jensen (2021) ‘Frictions of everyday mobility: traffic, transport and gendered confrontations on the roads of Accra, Mobilities, 16:4, 461-475, DOI: 10.1080/17450101.2021.1917969

- Ministry of Finance (2022). Ghana’s 2022 SDGs Budget and Expenditure Report

- Hart, J. (2016). Ghana on the Go: African Mobility in the Age of Motor Transportation. Indiana University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1zxz06q

- Quayson, A. (2014). Oxford Street, Accra: City Life and the Itineraries of Transnationalism. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11vc7z3

- Alimo et al (2022). Is public bike-sharing feasible in Ghana? Road users’ perceptions and policy interventions. Journal of Transport Geography. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2022.103509